By Rebecca Baum

I first encountered the terms pantser and plotter on a writing retreat in New Hampshire on Squam Lake. As dusk gathered and the loons wailed, a writer asked which approach I’d used for the middle grade novel I was working on. She went on to define the plotter as the writer who outlines a beginning, middle and end before the first keystroke of the novel itself; and the pantser as the thrill-seeking, fly-by-the-seat type. All they need is a snippet of a scene, glimpse of a character, or flash of setting — and they’re off!

I confessed to being a pantser. My middle grade book emerged in caffeine-fueled bursts, my outflow hindered only by my too-slow fingers. It was my first novel and the process of discovering the story as it was being written was unbridled fun. The downside (as early readers reported) were moments where the story felt rushed or where plot and character motivation didn’t always jibe. Unsurprisingly, that novel was never published. But it was a valuable exercise in showing up every day to slay the dragon of the empty page until eventually I’d hammered out over 60,000 words.

My novel, Lifelike Creatures, started as a pantser affair but morphed into a plotter-pantser hybrid. I started with a visceral sense of the landscape, lifted from my childhood in Cottonport, La. — fresh, turned earth and muddy fields stretching to the horizon, the stultifying heat of high summer, a gray sky both endless and oppressive. Within this rural setting a girl appeared, 13 years old, most comfortable with her toes in the mud. A boy, perhaps a brother, briefly bobbed into view then disappeared, replaced by the girl’s mother. Soon their relationship took shape, a claustrophobic constellation propelled by addiction, resilience, pain, and fierce love. The girl became “Tara” and the mother became “Joan.”

I brought these green shoots into a writing workshop. Each week, as I worked and reworked a chapter, or even a few pages, the contours of Tara and Joan’s relationship solidified. The details of their home came to life as did the intimacies and tensions of their days. The workshop facilitator challenged me to widen the lens and discover a larger community or cultural conflict against which Tara and her mother could struggle and transform — or falter and fail.

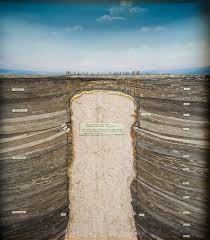

He also encouraged me to write a chapter outline, nudging me into the realm of the plotter. An early outline, which is very different from the final novel, has Tara losing her way in a salt dome mine during a visit to Avery Island (home of Tabasco Pepper Sauce ). Salt domes are massive underground deposits, some as large as Mount Everest, which feature prominently in Louisiana’s geology. I’ve always found them fascinating and mysterious, an interest I share with Tara:

Before fifth grade, when her class had studied salt domes, she’d pictured the New Orleans Superdome made out of salt, buried a few feet below her front yard. But the teacher had explained that the domes were more like underground mountains, formed when an ancient seabed buckled up over millions of years through the surrounding crush of earth. The salt behaved almost like lava, flowing upwards until it capped near the surface. For a time afterwards, whenever Tara salted her food, she imagined tiny flecks of bizarre prehistoric sea creatures mixed in with it.

–Lifelike Creatures, pg. 36

So the impulse to somehow include salt domes in the story emerged early on, even before I’d plotted the larger conflict that would come crashing into Tara and Joan’s world. With salt domes on my radar, it was inevitable that I should happen upon the other geologic phenomenon of Lifelike Creatures, the one that became the larger conflict — a sinkhole. Turns out the two often go hand-in-hand.

State Exhibit Museum

Salt domes and sinkholes have made headlines in Louisiana several times over the years, most dramatically at Lake Peignur in 1980, when the drill from an oil rig barge punctured a salt dome beneath the lake. The miscalculation created a sinkhole, triggering an enormous whirlpool that drained the lake and even reversed the flow of a nearby canal, temporarily creating Louisiana’s tallest recorded waterfall.

More recently, the Bayou Corne sinkhole was precipitated by a collapse in the Napoleonville Salt Dome. Or more accurately, the wall of a hollowed out cavern within the dome, near the dome’s outer wall. The cavern was manmade, as are dozens of others nested deep within the dome’s interior. Adding to the mystique of these underground marvels is the fact that they are uniquely well-suited for storing hydrocarbons, natural gas, and even crude oil. If the earth shifts, the salt walls flex and flow. Integrity is maintained as long as the surrounding salt is of adequate thickness. It was not in the case of the Bayou Corne sinkhole. As a result, an entire community was displaced with many residents leaving behind what they’d assumed would be the golden years of retirement.

The sinkhole in Lifelike Creatures is modeled on this real-life industrial disaster. My fictionalized version not only connects the “small” story of Tara and Joan with larger, catalytic forces. It also mirrors the downward spiral of drug and alcohol addiction and the corrosive effects on the parent-child relationship. I’m fortunate to have a close friend who is a geologist. He generously shared his expertise, allowing me to plausibly plot sinkhole and remediation events that force Tara and Joan into “adapt or die” situations.

So pantser or plotter? Based on my experience with Lifelike Creatures, I’ve embraced a middle way. The tools of the plotter kept me grounded even as the chapter outline changed and evolved. The pantser’s spontaneity offered unforeseen gifts, including a pivotal moment that totally took me by surprise. Early readers have had no qualms about pacing or character motivation. And Tara and Joan were given what every character deserves — a plot integrated with their core desires and beliefs.

Rebecca Baum is a New York City transplant from rural Louisiana. She’s authored several short stories and two novels. The most recent, Lifelike Creatures, was published by Regal House Publishing on September 17, 2020. She is represented by Jeff Ourvan at Jennifer Lyons Literary Agency. She’s a cofounder of a creative studio where she is a ghostwriter, copywriter, and blogger. She lives in Greenwich Village with her husband and their cat.