Regal House Publishing Senior Editor, Pam Van Dyk, interviews Martha Kalin, winner of the Terry J. Cox Poetry Award, on the craft of poetry, winning the award, and advice for novice poets.

Regal House: We’d like to know how you got started writing poetry. What is your “poet’s origin story”?

Martha Kalin: I began writing poetry as a very young girl, so it seems as though poetry’s been part of me forever. It’s a bit of a mystery what drew me to poetry in particular, but I always loved the sounds of words, loved to be read to, and had an extended family of teachers and writers who encouraged me. I particularly loved writing limericks and other short forms. I even created a collection of my work, with the book divided into sections, one titled “Poems About Animals”, the other titled “Poems About Anything but Animals”! In school my favorite classes were always creative writing and I often would secretly write poems when I was supposed to be working on math problems.

Regal House: Who were/are your biggest influences as a poet and why?

Martha Kalin: There have been so many influences I could never name them all. In college I fell in love with English Romantic poets such as Wordsworth, Keats, and Shelley and American poets such as Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, T.S. Eliot, Wallace Stevens. In some cases the influence was because I shared a love for the beauty of the natural world, in some cases, because there was so much feeling in their poetry, I always felt transported. Over the years I’ve dipped into the waters of many contemporary poets and have loved many. About ten years ago I was fortunate to discover Lighthouse Writers Workshop, a non-profit center for writers in Denver, Colorado and became closely involved in the Lighthouse community. This has been a rich source of ongoing learning and support and has had a huge impact on my writing.

Regal House: What books, poetry or otherwise, are you currently reading?

Martha Kalin: I’m reading (and re-reading) Marie Howe’s beautiful poetry collection Magdalene, and Ocean Vuong’s stunning collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds. I just finished Natalie Goldberg’s memoir Let the Whole Thundering World Come Home and am slowly making my way through The Way of the Dream: Conversations on Jungian Dream Interpretation with Marie-Louise von Franz, by Fraser Boa.

Regal House: What does winning the Terry J. Cox Poetry Award mean to you?

Martha Kalin: It’s such an incredible honor to win the Terry J. Cox Poetry Award. As a poet, it’s often hard to know how one’s work is being received, or whether it speaks to people in memorable ways. It means so much that others appreciate my work and want to support me in finding a wider audience. I was particularly moved that the award was named for the father of Regal House Publishing’s Editor-in-Chief, who was a poet himself.

Regal House: Among the poems in your winning collection, How to Hold a Flying River, do you have a favorite or one that holds special meaning? Can you share why?

Martha Kalin: The poem “Between Your Sleep and Mine” has particular significance to me. It represents a point in time when I was consciously trying to move from writing short, and more traditional lyric poems toward longer (for me), more complex and layered poems. I was seeking to reflect more fully today’s world, the pain, strangeness and intensity, but also new forms of understanding. I began to develop increasing interest in experimental and hybrid forms that integrate poetry and prose and that make leaps into and out of dreams and the unconscious.

Regal House: Alice Walker once said, “Poetry is the lifeblood of rebellion, revolution, and the raising of consciousness.” What are your thoughts on what poetry does for the world?

Martha Kalin: I love this quote and feel deeply that poetry has tremendous power to speak the unspeakable. Poetry, can startle, shock, and break us open in ways that can lead to deeper compassion and connection with one another and the truth of our experience.

Regal House: Do you have a routine or process for crafting your poetry?

Martha Kalin: Yes! This may seem a bit weird, but I write most of my poems these days in my phone. I use it like a journal, but it works even better than a paper notebook, in that I almost always have it with me and can capture little fleeting images and lines that otherwise would be lost. I’ve never been adept at writing in a disciplined way, or at responding to prompts or assignments. I do best when I catch impressions and unexpected passing phrases that then stimulate my imagination. I take all these notes in my phone and mull them over and play with them. Eventually I’ll gather them to see whether anything interesting starts to arise. Only when I have something with a bit of sizzle for me do I begin to craft the lines into a poem. I usually work on a poem for quite a long time, sometimes even for years.

Regal House: Finally, what words of advice might you offer to those who are just beginning to write poetry?

Martha Kalin: I encourage anyone with an interest in writing to read widely and find poems that inspire you, delight you, or speak to you in an important way. Listen carefully to the rhythm and music of the language. Practice writing by imitating or just letting your imagination run freely. Take feedback from others you respect but don’t let criticism stop you from writing what you want to write. Search for your own voice, the voice uniquely yours. And then write fearlessly.

Martha lives and write in Denver, Colorado where she works for University of Colorado’s Department of Family Medicine, developing programs for vulnerable and high risk patients. Her recent publications include poems in Anastamos, Don’t Just Sit There, Inklette, Hospital Drive, Panoply, San Pedro River Review, and the anthology Obsession: Sestinas in the Twenty-First Century published by University Press of New England. Her chapbook Afterlife and Mango, was published by Green Fuse Poetic Arts in 2013.

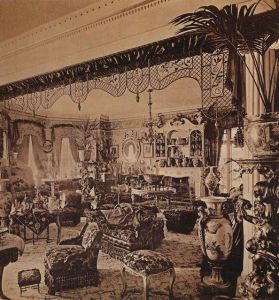

“Why,’ so many ask me, ‘write about this period?’ That is to say, 1860, and London, no less. I’m not English, and honestly, I wasn’t around then.

“Why,’ so many ask me, ‘write about this period?’ That is to say, 1860, and London, no less. I’m not English, and honestly, I wasn’t around then.

And it struck me, while indulging my fascination for all things Victorian by writing a novel about this most interesting time (remember, 1860 was also the year after Darwin’s theory of evolution crashed onto the scene) that some intriguing questions could be asked. What, I mused, would happen if the patriarch of this most Victorian of households were to lose his hold on it? What if he and his domestic influence were to fade? What would change?

And it struck me, while indulging my fascination for all things Victorian by writing a novel about this most interesting time (remember, 1860 was also the year after Darwin’s theory of evolution crashed onto the scene) that some intriguing questions could be asked. What, I mused, would happen if the patriarch of this most Victorian of households were to lose his hold on it? What if he and his domestic influence were to fade? What would change? JL (Judy) Crozier’s early life was a sweep through war-torn South East Asia: Malaysia’s ‘Emergency’, Burma’s battles with hill tribes, and the war in Vietnam. In Saigon, by nine, Judy had read her way through the British Council Library, including Thackeray and Dickens. Home in Australia, she picked up journalism, politics, blues singing, home renovation, child-rearing, community work, writing and creative writing teaching, proof reading and editing, and her Master of Creative Writing. She now lives in France.

JL (Judy) Crozier’s early life was a sweep through war-torn South East Asia: Malaysia’s ‘Emergency’, Burma’s battles with hill tribes, and the war in Vietnam. In Saigon, by nine, Judy had read her way through the British Council Library, including Thackeray and Dickens. Home in Australia, she picked up journalism, politics, blues singing, home renovation, child-rearing, community work, writing and creative writing teaching, proof reading and editing, and her Master of Creative Writing. She now lives in France.

I use a computer. One of the best things my mother ever did for me was pack me (and my older brother) off to Stott’s Business College in Melbourne for a summer course in typing. She’d gone there herself about forty years before, and I have to say the place did seem to hark back a bit. We had huge typewriters that were possibly 20 years old even in the 70s. Perhaps one of them still had my mother’s fingerprints on it. We all typed in rhythm – one-two-three, one-two-three – and we’d bring our finished paragraph up to the teacher to check. Any mistakes and we’d have to do it again. My brother, a post-graduate at the university at the time, kept making so many mistakes he began to cheat and not take his paragraph to be vetted. Then we’d begin to have a bit of a giggle, outraging the teacher who, it turned out, thought I was flirting with this boy. Ah, the 70s. Recall this ‘boy’ is and was six years older than me, but, hey, it must be the girl’s fault. Still, she blushed fiery red when she discovered our surname was the same.

I use a computer. One of the best things my mother ever did for me was pack me (and my older brother) off to Stott’s Business College in Melbourne for a summer course in typing. She’d gone there herself about forty years before, and I have to say the place did seem to hark back a bit. We had huge typewriters that were possibly 20 years old even in the 70s. Perhaps one of them still had my mother’s fingerprints on it. We all typed in rhythm – one-two-three, one-two-three – and we’d bring our finished paragraph up to the teacher to check. Any mistakes and we’d have to do it again. My brother, a post-graduate at the university at the time, kept making so many mistakes he began to cheat and not take his paragraph to be vetted. Then we’d begin to have a bit of a giggle, outraging the teacher who, it turned out, thought I was flirting with this boy. Ah, the 70s. Recall this ‘boy’ is and was six years older than me, but, hey, it must be the girl’s fault. Still, she blushed fiery red when she discovered our surname was the same.

Quill and the blood of virgins took me down a narrative path that I finally had to opt out of. It became too messy. Before computers became an essential writer’s tool, and when typewriters were my only other option, I wrote exclusively with a pen on yellow lined pads. I couldn’t imagine ever being able to write creatively on a typewriter, and I never did. But when computers seduced me into their world, I could no longer hold out. Previously, I not only hand wrote my drafts of poems and fiction, but I also typed them up afterward so I could then revise them. That involved further (multiple) rounds of typing and revising. Those of you who are writers know how many revisions are necessary before a draft becomes viable.

Quill and the blood of virgins took me down a narrative path that I finally had to opt out of. It became too messy. Before computers became an essential writer’s tool, and when typewriters were my only other option, I wrote exclusively with a pen on yellow lined pads. I couldn’t imagine ever being able to write creatively on a typewriter, and I never did. But when computers seduced me into their world, I could no longer hold out. Previously, I not only hand wrote my drafts of poems and fiction, but I also typed them up afterward so I could then revise them. That involved further (multiple) rounds of typing and revising. Those of you who are writers know how many revisions are necessary before a draft becomes viable. Since most people who will likely read this interview won’t know me, they may wonder, after learning about my novel

Since most people who will likely read this interview won’t know me, they may wonder, after learning about my novel

Teaching writing has given me many gifts. Maybe that sounds corny, but it’s true. Teaching requires that I make a deep study of masterful writing. In fact, the first writing class I taught was “Learning From the Masters: Techniques of the Literary Greats.” Of course, I had studied renowned authors in grad school, but now I had to go deeper. To prepare for the class, I examined how Hemingway constructed his dialogue so it sounds real, how Baldwin used imagery to create underlying meaning, what Grace Paley does to make us laugh. In identifying specific techniques and articulating for students what they accomplish, I have learned a tremendous amount. Ten years later, I’m still teaching the “Learning From the Masters” course and it continues to feel fresh.

Teaching writing has given me many gifts. Maybe that sounds corny, but it’s true. Teaching requires that I make a deep study of masterful writing. In fact, the first writing class I taught was “Learning From the Masters: Techniques of the Literary Greats.” Of course, I had studied renowned authors in grad school, but now I had to go deeper. To prepare for the class, I examined how Hemingway constructed his dialogue so it sounds real, how Baldwin used imagery to create underlying meaning, what Grace Paley does to make us laugh. In identifying specific techniques and articulating for students what they accomplish, I have learned a tremendous amount. Ten years later, I’m still teaching the “Learning From the Masters” course and it continues to feel fresh. Writing

Writing

What do you read that people wouldn’t expect you to read?

What do you read that people wouldn’t expect you to read? Anything that helps us to understand and connect with others is important, and learning other languages is most definitely a window into other people and different cultures. The way we express ourselves in our languages is hardwired into our brains, and if we can speak other languages, we can have insights into the thought processes of other people that we otherwise wouldn’t have. I loved writing Secrets in Translation, because I could use my Italian, which I began speaking when I grew up in Southern Italy as a little girl. It made me feel at home again! I speak other languages, as well, but Italian is the language of my heart.

Anything that helps us to understand and connect with others is important, and learning other languages is most definitely a window into other people and different cultures. The way we express ourselves in our languages is hardwired into our brains, and if we can speak other languages, we can have insights into the thought processes of other people that we otherwise wouldn’t have. I loved writing Secrets in Translation, because I could use my Italian, which I began speaking when I grew up in Southern Italy as a little girl. It made me feel at home again! I speak other languages, as well, but Italian is the language of my heart.